I was posted to Bangladesh in 1976, accompanied by my family who accepted the upheaval and moved without a murmur! Cassandra, our last child was born in Dacca. We left in 1980 and I then spent a year at Reading University on an MSc course in development studies, sponsored by OXFAM.

We lived in Dhanmondi, an old suburb of Dacca, in a bungalow set in a large garden planted with mango and jackfruit trees. One room became the OXFAM office. We were joined by Jim Clevenger, to concentrate on land issues, and later by David Williams, a civil engineer. Caroline acted as our secretary. Choudhury was our office manager and for transport we had an old Land Rover, donated by the British High Commission, plus a driver, Saleem Ahmed.

With the expansion of our programme to include work with landless groups we had an annual budget of £150,000, and we recruited two Bangladeshi field officers: Julu Badradoza and Marfuse Khan who were provided with motorbikes.

As the Bangladesh Field Director, I was responsible for the OXFAM contribution to the country. Later I was also given the responsibility of Burma. I related to Michael Harris, the Overseas Director in Oxford, usually through the Bangladesh desk officer, Sheena Grosset.

Our brief was to provide support to the poorest in the country. However, my first priority was to establish good working relations with the NGOs already supported by OXFAM: the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC); Gono Shastrya Kendra, the leading community health project; AMREF; and Concern, the Irish volunteer NGO.

This was an excellent foundation to build on but at least at first it was a great challenge, particularly for someone new to the country, relating to very experienced and committed projects and trying to grasp the myriad complexities of the country.

One only had to leave our house to be aware of the population – about 80 million in a country the size of Wales. About half were either landless or had the smallest of plots. The government was relatively inexperienced having taken over from Pakistan without preparation after the war. Of government development assistance only about 15 per cent went to this sector, most of which was donated by foreign governments. There was a coup attempt by the army in 1978.

Suspicion of foreign workers, particularly the missionaries, grew but this didn’t create great difficulties, which was just as well because the missionaries provided healthcare and education to many very poor communities. But everyone who was using pyscho-social methods (based on Paulo Freire’s work) caused suspicion. One contact told me he had been arrested and interrogated. The chair he was tied to came from Israel, so too the instruments used by the interrogators.

The three of us travelled widely over terrible roads and tracks and often by boat, meeting existing projects, giving advice, monitoring projects and discussing new project ideas.

Much freight was moved by river boats and when driving one could see the sails of the boats over the flat countryside (today the sails have gone and the boats are powered by diesel engines).

Here is a brief summary of the main projects we supported while I was based Bangladesh:

*Slum clearance

*Community health

*Rural development

*Training

*Disaster relief

* Co-ordination (ADAB)

Slum clearance: A year before we arrived, the government was embarrassed by the beggars and destitute people living in the city in makeshift shelters, and sometimes in drain pipes. It therefore forcibly moved them to sites in Demra, just south of the city, and to Tongi to the north. A third camp for Biharis at Mirpur was within the city. This was a joint NGO, GOB project.

Very little preparation had been made: only a few stand-pipes, few latrines, no housing. Added to these shortcomings was the lack of drainage which meant that both sites flooded during the rains. To add to the hardship, the opportunities for some work – such as rickshaw pulling, sweeping, etc. – were far less.

Our contribution was to install the OXFAM sanitation units in the camps – altogether 56 in total which met the sanitation needs of most of the communities. We visited the camps regularly to monitor the care of the units and Jim Howard, the OXFAM engineer based in Oxford, came regularly to check on the use of the units. Concern and other NGOs became involved in housing, training, healthcare and family planning.

We attempted to persuade the communities to take charge of the units’ maintenance rather than our having to employ cleaners. There was a moderate response to this.

It is true that we were all doing work that should have been the responsibility of the GOB. Nevertheless, we met an immediate need. (The camps are still there. But the original occupants have either died or moved on and the new occupants tended to use the camps as a city base for work).

Community health: Most of the projects we supported were involved in community health work, particularly the missions. But the most interesting and influential was Gono Shastrya Kendra, just north of Dacca. This was set up and run by Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury, a doctor, former Freedom Fighter, a public health activist and fiery charismatic figure. He pioneered the concept of paramedics in Bangladesh and schemes to get the people to support the paramedics by making small charges for treatment. Paramedics were trained to perform simple operations and also to weld doors and window frames.

A highly innovative development by GSK was to set up a factory making generic drugs and thus to provide medicine at a lower cost than imported drugs. The factory was funded by OXFAM among others.

GSK was constantly in need of funds, and we were keen to support the project. But Zafrullah didn’t make it easy for us. He made skimpy proposals and poor reports. Inevitably there were fierce arguments. We were caught in the middle between GSK and Oxford and in desperation Zafrullah would storm off to meet the overseas director in Oxford who would usually oblige. So often our role was reduced to that of a post-box. Another problem was that to secure his programme he would save surplus funds for future work and not declare them.

Other smaller health projects supported by OXFAM included: Rehabilitation Project for Paralysed Patients; Bollobpur Mission Hospital Tetanus Eradication programme; Patharghata Health Centre; Manikganji Family Planning Association; Baromari Dispensary; Christian Health Care Project.

Rural Development: About one third of the rural population are landless and work as labourers who cultivate the land of the more affluent landowners. Another third have less than an acre which is barely enough to provide subsistence. However, the land is amazingly fertile, replenished by silt brought down by the rivers, and if in the dry season it will yield plentifully with irrigation.

We concentrated on supporting landless groups to rent land and provide them with funds to buy irrigation equipment. They could therefore irrigate land in the dry season and grow wheat and vegetables. The snag was, however, that the more successful they became the less the landowners were prepared to provide the land.

Our closest link was with Zia Uddin, a young landowner, committed to working with the landless cultivators in his locality. He came from a Zamindar family who were appointed by the Colonial administration to collect taxes. To reach Zia we had to go on a long boat journey through the rivers and flooded fields.

My visits to him were always pleasurable as well as enlightening. We would sit in the evening on the edge of the large fish tank discussing our work and smoking a hookah kept alight by a small boy. A scene reminiscent of Tolstoy’s intellectuals grappling with the future of Russia!

Other landless projects supported by us included the Muktinagar Agricultural Co-operative Society with 80 members who cultivated 53 acres irrigated by six pump-sets. They had trouble with their bank and we therefore increased our fixed deposit to enable further drawings. Another project was the Atrai Tana Landless Farmers Co-operative Association, a central body for 28 landless groups. We provided a three-year loan to enable the association to buy three second-hand pump-sets for winter rice and wheat production.

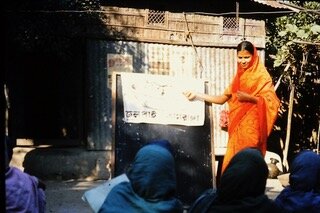

A literacy class - the corner stone of the BRAC programme

Our main support was channelled through the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) which was set up by Sir Fazle Abed after the war. BRAC is dedicated to assisting people to climb out of poverty through education, training and community health projects. When I first met Abed he was based in a small office. Now BRAC occupies a tower block and has become the largest NGO in the world. And it has set up a new university in Dacca.

OXFAM funded BRAC’s Sulla project in a remote area near to the Indian border. It was the first BRAC rural development project where they tested out new ideas. The programme is exclusively with landless and other disadvantaged groups. Its approach was through functional literacy programmes based on the ideas of the South American educationalist, Paulo Freire, and income generation. Being able to count and read are the first steps to breaking out of extreme poverty.

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, founder and now chairman of BRAC, delivering Bledisloe Lecture at the Royal Agricultural University

We also supported the BRAC Training and Resource Centre at Savar; Seva Sangha Street Boys Vocational Training Centre; Seven Villages; Women’s Self-Reliance Movement; Comilla Women’s Societies; Swallows Thanapara Project; Chourkhuli Fishing and Agricultural Co-operative Society.

As BRAC had become so powerful it was moving out of our league but we frequently consulted them and learned from their experience. In 2017 Sir Abed visited the Royal Agricultural College, where I was based, and lectured on the work of BRAC.

Training: Providing young people with a skill to help to find work beyond their villages is a good example. The Church of Bangladesh Ratanpur Agricultural Implement Repair and Training centre. This is situated west of the river Ganges near the Indian border.

The journey to Ratanpur was long and exhausting: by road from Dacca to the river; crossing the Padma/Ganges river in one of the ferries provided by OXFAM after the War, by road again and eventually by bullock car (our youngest daughter learned to imitate the squeaking sound of a bullock cart’s wheels).

Ratanpur provided training for about 15 boys equipping them to earn a living. The project was run by a priest/missionary, Tom Thubron, with the help of his wife, Di. We provided grants for a flour mill to help generate income, money for a wood store and a motor bike.

Tom came from Durham and at first worked down the coal mines. He then joined the Merchant Navy and progressed through further training to become a ships engineer. Finally, he decided on joining the church and after training sailed out to Calcutta to the Anglican mission. From there he was posted to Ratanpur where he set up this excellent centre and defended its interest like a bulldog. He had frequent tussles with anyone who tried to interfere. Tom and the Bishop of Dacca had a particularly difficult relationship and I was asked to mediate between the two.

Disasters: In 1978 came the influx of 200,000 Burmese Rohingya refugees into Cox’s Bazaar and 13 camps were set up were set up along the coast. This was the first big disaster during my time in Bangladesh. It was a huge influx given the poverty of the area and the lack of resources. They had been driven out by the Burmese army and local Burmese on the grounds that they were Muslims, and not citizens of Burma, and were taking Burmese farmland.

The GOB and UNHCR mounted a relief programme with temporary housing, healthcare, water, and feeding centres. We provided 20 sanitation units and helped with nutrition surveys. It soon became clear that the rations were inadequate and we pressed for these to be increased, but both UNHCR and the GOB were reluctant to do so, in the hope that the refugees would soon return to Burma. The nutrition surveys showed that the death rate in the camps was 8.5 times the average for Bangladesh. We helped with international publicity. This caused a major furore; the GOB was suspicious of us for stirring up the situation but the eventual result was improvements to the conditions in the camps.

Diplomatic efforts to guarantee the Rohingya a safe return have so far failed. Cox’s Bazaar, with its beautiful beach, is a holiday resort with very few opportunities for work and was the worst place for the refugees, deprived of their plots. They had no option but to depend on handouts.

I visited northern Arakan in 1978 with the Burmese Red Cross – a long journey by road and boat. The area was terribly run down and the local hospital virtually abandoned. An operating table was propped up on bricks. It was smeared with congealed blood. I met the army commander who expressed intense dislike of the Rohingya. “We tread on them as you would a snake,” he said cheerfully.

More recently, a further influx of people from Arakan have arrived, as a result of renewed pressure from the Burmese army and local people. Aung San Suu Kyi supported the government action claiming that it was not a case of genocide. The issue could have been be resolved if the Rohingya were given Burmese citizenship and assisted to resettle back in Arakan.

While working in Cox’s Bazaar we visited the ‘King’ of the Maungs, who lived in the Chittagong Hill Tracts just a few miles inland from Cox’s Bazaar. Their ‘palace’ was a simple building in a small compound. He and his wife were courteous and welcoming and we enjoyed staying with them. They kept an elephant in the compound presumably for ceremonial functions. Our children were given a ride on it much to their excitement.

Association of Development Agencies in Bangaldesh (ADAB): Co-ordination between the many foreign NGOs was always a problem. ADAB assisted where it could. It had a library and held talks and briefings. I doubt if it made much of an impact because of the individualism of many NGOs who tended to pursue their objectives without a great deal of thought for others. It was welcome nevertheless.