by Anthony Speaight

In late 18th century London there lived my ancestor whom our family knows as William I. He is recorded as having been a brewer. The fact that he was able to have his portrait painted by a leading artist of the day, James Northcote RA, and his stylish image in it, suggests that his business must have flourished.

He and his wife, Elizabeth, had no fewer than 12 children, from whom are descended the Speaight family clan which has increased and multiplied. This article concerns two of his descendants, James and Joseph Speaight, both remarkably talented musicians[1], and their branch of the family.

Amongst William I’s children was my direct ancestor, whom my branch of the family know as William II, the proprietor of a family printing business. One of his older brothers was christened Charles: the musician brothers were descended from his line. There was nothing in the brothers’ parentage to give a clue to the remarkable musical talent which would appear.

Charles Speaight the watch case maker

Charles, the son of William I, was born in Clerkenwell in 1787. Just after his 15th birthday he was apprenticed for seven years to a maker of watch cases[2]. As was customary at that time the apprenticeship was formalised by a deed of indenture containing stringent provisions: these included prohibitions during the apprenticeship’s seven years against playing at cards or dice, against “haunting taverns”, and against committing fornication. They also prohibited him from marrying; he did not wait many months after its completion before he did get married – to Elizabeth Greenwood from Spitalfields.

Within a year of the marriage Charles the watch case maker and Elizabeth had twins, Elizabeth Ann and William John; and then one more child, a boy born in 1816, who was also christened Charles[3]. By the time of the birth of their twins they would seem to have been living in Bethnal Green.

Elizabeth Ann married George Busby. They are the direct ancestors of Peter Busby, who supplied much information for this article.

Charles Speaight the weaver and his relations

Charles junior became a weaver, thereby continuing a family connection with textile and garment skills stretching back to forbear Speights in Yorkshire. In 1836 he married Susannah Eggington, who had been brought up locally, and herself learned the same occupation, being described in the 1851 census as a hand loom weaver. In their married life they lived firstly at Scott Street, and later at 85 Church St, both in Bethnal Green.

Charles the weaver’s brother William John was also a weaver; as was his wife Hannah, whose maiden name was also Eggington, that is the same as that of Charles’ wife. It needs little speculation to imagine that the two brothers married two sisters. Other relations also lived in, or near, Bethnal Green. We may thus infer that the weavers of Bethnal Green were a close family.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries silk was one of London’s biggest industries. It was centred on the area of Bethnal Green and Spitalfields. The tradition of silk weaving there was associated with the arrival in the late 17th century of Huguenot migrants, who were heavily dependent on the silk trade. The design of many of the houses in Bethnal Green bespeak the requirements of the silk-weaving industry – large windows to let adequate light into the workrooms, which would typically be on the upper floors of houses which had a dual residential and industrial purpose.

A fascinating insight into the working life of William John is afforded by the law report of a case tried at the Old Bailey in 1835. The defendant, a certain John Davis, was indicted for stealing some 20 yards of silk from William John Speaight. The evidence was that the silk was worth £6, which would be about £750 today. The theft was committed at 1, London Street, Bethnal Green, a building which conformed to the typical mixed residential and industrial use. William worked on his loom in an upstairs room of this house. In the same workroom there also worked a young woman, the Hannah Eggington who married William John a couple of years later: she seems to have been a step-daughter of the owner of the house[4]. William John gave his address as in the same street. That William John owned the loom is indicated by the fact that he could charge others for its use. The defendant paid him 3 shillings a week for the use of the loom, and for tea. Davis was convicted and sentenced to be transported for seven years.

Charles the weaver and Susannah had eight children. At least one daughter continued in the occupation of weaving. Another daughter’s occupation was described in the 1851 census as wine drawer, and a third’s as daily servant. The occupations of two of their sons, however, moved in a new direction, both becoming professional violinists. These were James George Speaight, born in 1844, and his younger brother, William Edward.

James George at the age of 21 married Fanny Cook. Their union gave birth to two remarkable sons, who inherited musical talent from their father.

James Speaight the child prodigy

Their eldest child, born on 30th June 1866, another James George, who was known in the family as Jimmy, was a child prodigy[5]. He learned the violin from his father by ear. It was said that after a single hearing he could play even the most complicated compositions. By the age of 5, if not when he was still only 4, in a manner reminiscent of the Mozarts his father arranged for him to play in public. The family moved to the United States: in 1871 there is a record of residence in New York City of the father, mother, young Jimmy, his infant brother Joseph, and a Margaret Speaight aged 52[6]. There for three successive years he played in New York in a variety entertainment “Grand Spectacle of the Black Crook”, in which he was the chief attraction.

An American source contains this description of him:-

“... preternaturally large in head and small in person ....

Scarcely larger than the violin he carried, dressed in a bright court suit of blue satin, with powdered wig and silken hose and buckled shoes, like a prince in a fairy tale, he seemed the slightest mite of a performer who ever stood behind the foot-lights. His hands were scarcely big enough to grasp his instrument; his arms and his legs were not so thick as his bow; a bit of rosin thrown at him would have knocked him down; and he could have been packed away comfortably in the case of his own fiddle.”[7]

Not only did he play solos on the violin; he conducted a large orchestra, standing on a pile of books so that he might be seen by the musicians he was leading.

In the autumn of 1873 after playing in New York, his father took him to Boston. There for several days he gave further performances and led the orchestra of the Boston Theatre. After the matinee performance on the 11th January 1874 the theatre manager noticed “a look of fatigue and an air of languor” as he came off the stage. James claimed that he was fine, but sensing that he was not the manager insisted that his father should not bring him to the theatre for that evening’s performance. Accordingly, father and son remained at their lodgings and retired early, James still saying that he had no ill feeling.

Sometime after, the father was awakened by his son’s voice and distinguished the words: “Merciful God, make room for a little fellow!”[8]. The father, supposing he was speaking in his sleep, tried to rouse him, but could not do so. Then to his grief and horror he realised that his son had died. He was just seven and a half years of age.

Many people attended the funeral, including the entire troupe at the Boston theatre. He was buried in Boston Commons.

The local coroner held that the cause of death was, in medical terms, a heart attack. But some commentators attributed the tragic demise to an excess of attention at so young an age. The theatre historian Laurence Hutton wrote:

“That he was passionately fond of his art there could be no doubt, or that he lived only in and for it, and in the excitement and applause his public appearances brought him; but that his indulgence of his passion without proper restraint was the cause of the snapping of the strings of his little life, and of the wreck of what might have been a brilliant professional career, was plainly manifest to every physician, and to every mother who saw and heard and pitied him.”[9]

James’ life and tragic early death inspired a short story by the American novelist, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, entitled “The Young Violinist”[10].

Years later there was composed a tone poem for orchestra entitled Vita Brevis. On its front page were inscribed these words of the German romantic writer Jean-Paul Richter:

“There are souls which fall from heaven like flowers, but ere they bloom are crushed.”

The composer of this page was Jimmy’s younger brother, Joseph, who had been aged 5 at James’ death.

The family after James’ death

After young Jimmy’s death the family returned to England. His mother, Fanny, gave birth to a third child, another boy, three years later. But in the following year we find James, the father, re-marrying. It could be that Fanny died in the childbirth of her third son. With his second wife, Jane Amelia Whitley, James had a daughter, before James died at the unusually young age of 39. In keeping with this family’s traditional closeness, Amelia Jane then married James’ younger brother, William Edward.

The Dolphin, Bethnal Green

By this time Charles the weaver had left the silk trade, which went into decline in London in the second half of the 19th century. He moved to running what was described as a beerhouse; and in 1874 became the licensee of The Dolphin, a pub in Church Street, Bethnal Green, which had been a haunt of Huguenots since the early years of the century. Perhaps this move may have been influenced by the recollection that his grandfather had run a successful brewery business.

After his return from America James followed his father into the licensed trade, becoming the landlord of the Coach and Horses in the Mile End Road. Following his death, his brother, William Edward, who was to marry his widow, took over this pub. Both these professional violinists also worked as directors of music halls.

Another member of the family to take up running a pub was Elizabeth Ann, with her son then taking it over. All told, it is estimated by Peter Busby that more than a dozen of Charles the weaver’s sons, grandsons, sons-in-law, nephews and great nephews would become publicans. One who did not was the other brilliant musician, Joseph.

Joseph Speaight the composer

Joseph William Speaight was born on 24th October 1868. He studied at the Guildhall School of Music, where he later became a professor. He also taught at the Trinity College of Music in London. He played both the piano and the organ.

He married Laura Chambers. They seem to have lived much of their married life in Streatham.

He composed voluminously. His work included two symphonies, a piano concert and many other pieces for full orchestra; piano quintets and quartets, string quartets and much other chamber music; pieces for solo piano; many songs; and even a march for a military band.

On 30th August 1917 in the very first season of the Prom Concerts held at the Queen’s Hall the programme included the world premieres of two orchestral pieces from his work “Some Shakespeare Fairy Characters”: the items were “No 3 Puck Word” and “No 4 Queen Mab Sleeps”. They were played by the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra and conducted by himself. Other works in that concert were by Schumann, Verdi, Dvorak, Schubert, Liszt and Berlioz.

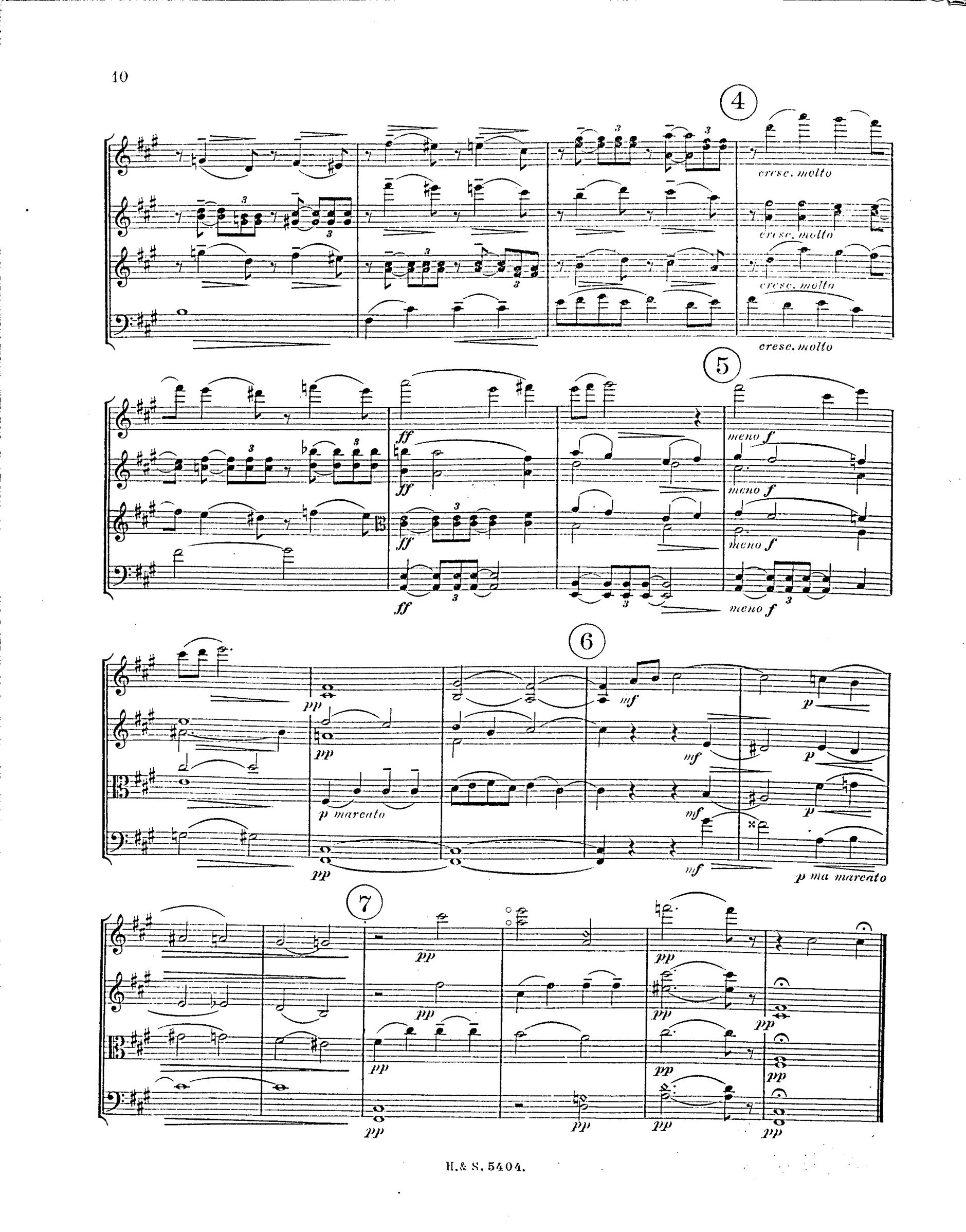

This score of ‘The Lonely Shepherd’, the second and shortest piece of The Fairy Characters, is reproduced here by courtesy of the British Library. Margaret Hebblethwaite has been searching the archives for Joseph’s compositions and struck gold at the British Library. They have the scores of thirty-three of his works and allowed us to scan the score of The Fairy Characters, written for a string quartet (1st violin, 2nd violin, viola and cello). The Library has two recordings of this piece and is having them digitised. The copies will be made available to us. The Lonely Shepherd is the name of a walk in the Brecon Beacons. The walk passes through the Clydach Gorge and Shakespeare was so inspired by the mystical properties of the Gorge that it inspired him to write A Midsummer’s Night Dream.

In the following season of the Prom Concerts the programme again included a world premiere by Joseph Speaight. This was entitled “Joy and Sorrow”, an orchestral tone poem. On this occasion it was conducted by Henry Wood, and again played by the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra.

Amongst his work which can be found on the internet are two songs, “John Cook and his Mare”[11], and “Going to St Ives”[12]. Other works of which sheet music has been located are three solo piano pieces, “Legends”, “Revellers on the Village Green” and “Nymph Dance”. Some of these piano pieces were played in Witham House by Michael Maxtone-Smith in November 2021.

He lived to the age of 79, dying on 20th November 1947 in Ware. He was survived by a daughter Freda Evelyn Pryke, who lived until 1977; Freda’s husband died as recently as 1990. They had four children.

[1] For first teaching me that the composer Joseph Speaight was, as she put it, “one of ours”, and for providing much other information, I am deeply grateful to Saira Holmes.

[2] For the information about Charles and Elizabeth’s family and succeeding generations of that branch, I am grateful to Peter Busby, a descendant of their daughter Elizabeth Ann.

[3] For some of the information in this paragraph I am indebted to research was sent to me some years ago by a distant relation, Dorothy De Ville, who is descended from William I’s last child, Edward.

[4] The owner was a Mr Thomas Smith. In her evidence Hannah Eggington described him as her “father-in-law”; but as she was single at the time, it may be that he was what today would be called a step-father.

[5] Web page sources (accessed 27th December 2021): https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Speaight-3

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2007/12/14/james-speaight-forgotten-child-prodigy. I am indebted to eter Busby for having located this and another source on the musician brothers in the New York library’s website.

[6] Common sense suggests that she must have been a relation, but I have not traced any relative of this name.

[7] “Curiosities of the American Stage” Laurence Hutton 1890

[8] Or according to a contemporary newspaper report, “Gracious God, make room for another little child in Heaven”

[9] op cit

[10] Text at https://www.nypl.org/blog/2007/12/14/james-speaight-forgotten-child-prodigy (accessed 27th December 2021)

[11] https://imslp.hk/files/imglnks/euimg/b/b9/IMSLP599844-PMLP964887-1_Speaight_john_Cook.pdf.pdf

[12] https://imslp.eu/files/imglnks/euimg/6/67/IMSLP599421-PMLP964179-1_Speaight_going_to_st._ives.pdf.pdf