Professional Life in Bangladesh and Africa

Bangladesh

OXFAM then offered me a job as Field Director in Bangladesh. I took the whole family to live in Dacca and there we had four memorable years. The country was recovering from the shattering civil war and we worked closely with organisations which had grown out of the war such as Gono Shasthaya Kendra (the People’s Health Centre) which pioneered the development of barefoot doctors in Bangladesh, and the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, now the largest NGO in the world and still under its founder and now chairman, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, a man of the highest ability.

I learnt a great deal in Bangladesh about working with the poorest of the poor. It was my first experience of deep poverty and the dignity of marginal people deeply impressed me. Their situation was often shocking and appalling.

We worked with the slum dwellers, many who had been forcibly resettled in camps, landless labourers, marginal farmers, and in 1978 the first wave of Rohingya refugees flooded in from Arakan, Burma. I also visited Arakan with the Burma Red Cross travelling up the country by boat. The Rohingya were pitifully poor and the Burmese army treated them mercilessly. ‘We crush them under our heels as if they were snakes!’ the commanding officer told me.

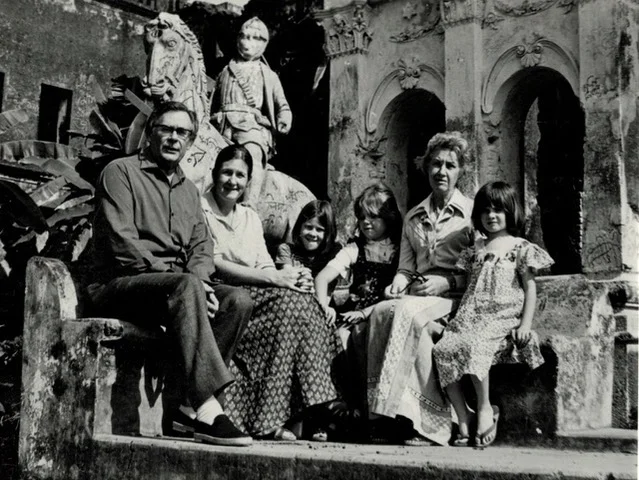

Visit to the ruined Sonargaon Palace on the Ganges in Bangladesh with my parents-in-law, Patrick and Sonia Bird. Three of our daughters are with us: (L-R) Charlotte, Harriet and Jocasta. Cassandra was born later in Bangladesh.

The Bangladesh government and UNHCR were determined to ‘encourage’ these wretched people to return to Arakan. I doubt if many did and now there has been a new influx and even less chance that they will ever be repatriated. They have a terrible future, with little hope.

This is a gun emplacement in the Bangladesh war of liberation from Pakistan in 1971. While the country was victorious it was shattered. We arrived in 1976 as the country was beginning to recover and we had the privilege of working with a number of highly committed Bangladeshi development groups. © Getty Images

Rohingya refugees fleeing from Myannmar.

The 2017 influx of Rohingya refugees. Resettling them will be a daunting task.

Not only was the work fascinating but we had a full and happy family social life which gave us great pleasure, opening our lives to a far wider community. We made many friends and are still in contact with them: David and Dorothy Catling, Edward and Mavis Clay, Alan and Janet Montgomery (Janet died and Alan has married Flo), Tom and Di Thubron, Brendan and Alison Parsons and Fazle Hasan Abed (his wife Bahar died tragically from childbirth and he has since remarried). My great friends Aengus and Jack Finucane have died following retirement in Ireland.

I miss particularly Aengus. He was CEO of Concern in Bangladesh and one of the founders of Concern in Biafra. A Roman Catholic missionary of the Holy Ghost Order and 20-stone former rugby player, he was tremendous fun, knocking back vast amounts of whisky without turning a hair. While we were good friends, Aengus was not too enthusiastic about OXFAM head office which he dismissed as ‘too fecking pious’. He was our youngest daughter’s godfather. He had to ‘consult’ Rome about this involvement with the Anglican world, but amazingly permission was granted within an hour or so.

We left Bangladesh with much sadness in 1980 and after completing a year’s MSc course at Reading we were posted to Nairobi as OXFAM rep in East Africa.

For more detail on my fieldwork in Bangladesh, please click here.

The fertile north of the country in the monsoon.

Africa

I flew out ahead of my family and took over our house from my predecessor, a bungalow in a quiet suburb of Nairobi. The OXFAM office was in Westlands and I remember the scent of flowers from a stall outside.

At first, I was responsible not only for Kenya but also Sudan and Uganda. I travelled widely in the region mostly by Land Rover over terribly rutted roads but I did learn to fly. Our work was largely targeted at small farmers and herders, assessing applications for grants and monitoring progress.

Well digging in Southern Sudan.

Initially I spent much time in Southern Sudan. The civil war between the north and south of the country had come to an uneasy end and we were able to work with the refugees from Uganda, Juba hospital and the pastoralists living on the grazing ‘toich’ lands adjacent to the Nile.

A western educated government official took me out to meet his family at their cattle camp. He wore a smart blue suit and a colourful tie; his brothers were naked and covered with white ash to deter the many insects in these grazing lands. They belonged to an ancient world far distant from the world of my companion. Families send their youngest sons to be educated but as they inherit no livestock they are unable to influence the pace of change.

We fielded a team of engineers to assist the refugees sink wells and in Juba, the capital of the south, we improved the sanitation of Juba hospital, a filthy run-down place with a high incidence of cross-infection. At the far end of the hospital compound a corner had been fenced off with barbed wire to form an isolation area of people with infectious diseases. Also in the compound were mentally and physically disabled people who scuttled around like crabs. At one end of the compound was a pile of hospital waste – soiled bandages, empty medicine bottles, used syringes. A refuse pit of humanity, and the most terrible scene I have ever witnessed.

The Khartoum government had decided after the war to abolish the semi-autonomous Southern Sudan and give each province of Sudan a local government. The government no doubt wished to weaken the south which is ethnically different from the Arab north. They distributed arms to some of the southern clans. Inter-tribal conflict resumed and it became increasingly dangerous to work there.

Sudan remains a beautiful country. On one journey we stopped at a grove of trees and sitting on rocks men were playing the Sudanese finger harps. I was accompanied by an eccentric American anthropologist clad in riding breeches. She hailed the men but they ignored us. An arcadian scene.

Driving through from Sudan to Uganda we would stop at the Verona Fathers’ Ombachi Mission at Arua. Several weeks before my last visit (in 1981) there had been a massacre in the mission chapel carried out by retreating Amin troops. People had taken shelter in it and 86 of them were gunned down. All was peace again when we arrived. The only sign that there had been a massacre was blood-stained carpet. Later I met one of those who was trapped in the chapel. ‘I hid under a pew and watched, out of the corner of my eye, a gunman approaching. His eyes were ablaze with fury. But thank goodness, he must have assumed I was dead and moved on.’ The Verona fathers kept the schools and hospitals of Uganda throughout the years of conflict.

Karamoja in north-east Uganda was just recovering from a famine and I spent much time there with our team which included Brian Hartley, an ancient and eccentric agriculturalist, and an endless source of knowledge on East Africa where he had worked all his life. He spoke half-a-dozen East African languages learnt, he said, from numerous lady friends ‘on the pillow’. We pulled his leg: ‘Your vocabulary must have been pretty limited and mostly confined to parts of the female anatomy!’ He chuckled in response.

The Karamojong are tall, powerful people, scantily dressed. Their world had been turned upside down when one of the Karamojong clans raided the police arms store. They, along with the other Karamojong clans, had lost vast numbers of livestock in the famine. They used their increased fire-power to steal stock from the other clans, thus perpetuating the famine.

The country was austerely beautiful, rolling grasslands populated by much game, including beautiful herds of oryx moving swiftly and smoothly through the bush, and semi-nomadic, heavily armed pastoralists, with the Didinga hills shimmering blue in the heat beyond the Sudan frontier. The herdsmen had largely retreated to camps as a result of the famine. In the bush, one had to watch out for bandits and I was twice ambushed at gunpoint by ragged desperate men who held me at gun-point flat on the road; and driving up from Kenya to Sudan a soldier said, quite casually, ‘I could kill you’ when, without thinking, I crossed the frontier – by no more than a foot.

But increasingly we concentrated on support to the livestock communities in Turkana in northern Kenya, assisted by Brian Hartley and Dick Sandford who was later to make a major contribution to FARM Africa.

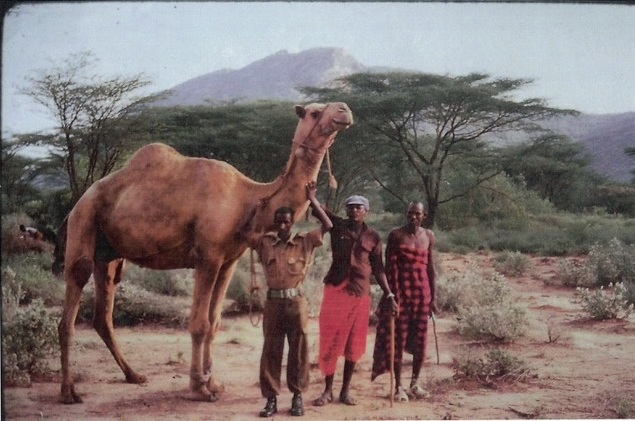

The Turkana tribe had migrated from the Nile to Turkana many hundreds of years ago. They are tall, fine-looking and the men wear mud-packed painted head dresses. The pastoralists had lost livestock – camels, cattle and goats – through the drought and famine and were living in relief settlements and fed by the World Food Programme. We and others helped them re-stock and return to the more viable life as pastoralist. We provided veterinary training, rehabilitated wells and demonstrated techniques for using the very limited rainfall to irrigate small areas for crop production.

One of the first ventures was a project to improve the productivity of Turkana camels who lacked the milkiness of camels from other areas. We recruited a young European woman, D, to help us. She belonged to a rootless expatriate community which had various ways of surviving in Kenya. But she was a skilled camel worker and from her base in the bush set up a centre for the project and was kept company by Chui, a wonderful dog we had passed on to her. He loved their hunting expeditions and met his death choking on zebra skin, one of the many she had shot.

D on safari in northern Kenya with her camels

D worked with us for a year and helped us find ways of working with camel herders. Much later, driving home one night her Land Rover overturned on the pot-holed road and she was killed outright. Letters from her many lovers, female as well as male, were scattered all over the bush. A friend of mine collected the letters and destroyed them. We were all greatly saddened by her death. She had a pioneering spirit which was largely being lost as ‘development assistance’ was becoming more professional and serious.

I wonder now how much we achieved. But we did provide much support to many communities and we were a presence and a witness in a time of conflict.

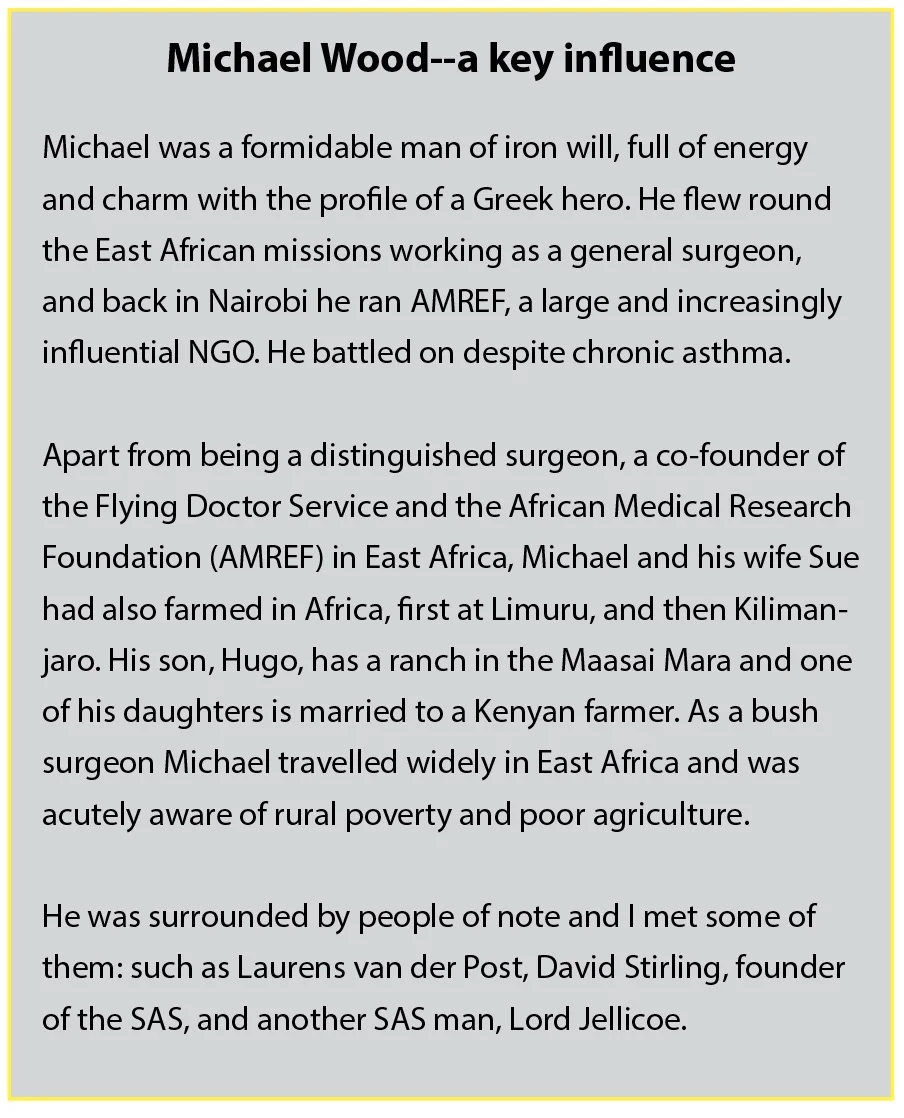

My life was changed by Michael Wood, a founder to the Flying Doctor Service and the African Medical Research Foundation (AMREF).

Sir Michael Wood (left) and I worked together to launch FARM Africa. Here he is with Jasper Evans, of Rumuruti ranch, northern Kenya, where we set up our first camel development project.

Michael worried me at first by bypassing our office and sending his requests for funds straight to Oxford. Finally, I said to him that we could not even consider assisting AMREF if he operated in this way. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said with a smile. ‘I will work direct with you in future.’ And he did. I also used to worry about his use of the phrase ‘Go an extra mile’, adapted from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount and the Roman Impress Law, but I can now see how wise and relevant it is.

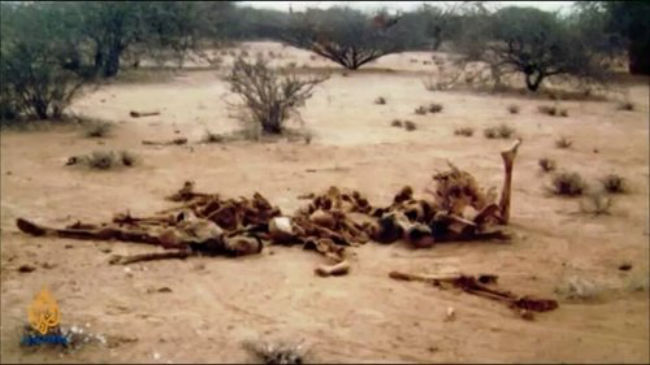

The tangled human remains of the Wajir massacre, about to be bulldozed into a pit and buried. This terrible event brought Michael Wood and me together as a working partnership to start FARM Africa.

In the fourth year of my time as the OXFAM rep there was an appalling massacre in Wajir district in the North Eastern Province of Kenya, primarily inhabited by ethnic Somalis. While the numbers have never been officially recognized, at least 200–300 Degodia Somali men, who did not possess Kenyan papers, were rounded up by Kenyan security forces and taken to the Wagalla airstrip where they were starved of food and water for five days before being burnt alive (I saw photographs of the bodies which were cleared off the strip by a fork-lift truck). This was clearly carried out on the orders of the District Commissioner who sat in his Land Rover watching the massacre. The huts of the Somali community living around Wajir were also burnt and many were killed, the wells sealed off and the people prevented from going to the mission hospital.

Michael had been alerted to the massacre by Sister Annalena Tonelli at the Wajir mission hospital and he suggested I join him on a reconnaissance. The town had been sealed off by the police and Michael and I had intended to find a way in with medical supplies for the mission, relying on Michael’s prestige in Kenya and OXFAM’s international reputation. Michael suggested we worked together on this.

I contacted my OXFAM boss, Michael Harris, for permission to proceed. I feared that we might get expelled from Kenya. To his great credit Michael said, ‘get in your Land Rover with Michael Wood and go'.

We packed our vehicle with medical supplies and drove off. However, at the Wajir district border we were stopped by the police and held for 24 hours in a corrugated iron shed. We sat in great frustration in the station. We could hear urgent calls being made to Nairobi.

As we waited to hear our fate, Michael, who seldom spoke about himself, said: ‘I’m retiring from AMREF in a year. I have concluded after a life’s work as a surgeon in Africa that food is the best medicine. I now want to start an initiative to tackle the problem in new ways.’ I jumped at this: ‘I finish my contract with OXFAM next year. I too want to concentrate on food production. May I join you?’ This was the beginning of FARM.

The following morning, we were escorted back to Nairobi by the police. We started lobbying the government and the diplomatic community, and after several weeks OXFAM, AMREF and other agencies were allowed to return to Wajir, thanks partially I think to Michael’s great prestige in East Africa. One of our first actions was to charter a DC3 and send up supplies to Wajir.

The Wagalla massacre represents the worst human rights violation in Kenya’s history, but it took the Kenyan government until 2000 to acknowledge publicly any wrong doing on the part of its security forces and the victims’ families have still not been compensated. It later emerged that the Wajir operation was carried out on the instructions of the President’s Office in Nairobi but it was said to have ‘got out of hand’.

Michael asked friends in the UK to register FARM as a company limited by guarantee. Securing registration in Kenya proved more difficult. Michael phoned the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance, 22 times to ask for a meeting to discuss our initiative. There was no reply, which was surprising because Michael knew the Permanent Secretary well and had treated his son. Finally, he went down to the PS’s office and sat outside his door until the PS arrived. The black mark against our names from Wajir might have been the problem but registration was granted. A great lesson in persistence.

FARM Africa

Michael built an office in the garden of his house in Karen and persuaded the British High Commission to loan us an old Land Rover. He broke into his pension fund to get us started.

Our organisation was called Food and Agricultural Research Mission (‘Mission’ shortly changed to ‘Management’). The name amused those who were close to Michael and aware of his preference for working with people he knew. AMREF was known as All Michael’s Relations and Friends and they immediately said how could FARM be called anything else – it clearly stood for Friends and Relations of Michael!

Michael’s circle of friends was indeed helpful and we drew in other contacts as well such as Sir Peter de la Billiere, of Gulf War fame, and an old family friend. Peter was a great asset to FARM but he and I did not work well together. On one occasion in Addis Ababa, after a pretty pointless argument, we both set off to the local running track to cool off. To avoid seeing each other too much we ran in different directions, clockwise and anti-clockwise. I passed him several times and then he disappeared. Perhaps he had had a heart attack as a result of his confrontation with me! I went to look for him. He hadn’t gone far: I found him running up and down a flight of steps as a keep-fit exercise. Later he apologised gracefully for his ill-humour and indeed we remain good friends to this day.

I started work with FARM in September 1985. Shortly afterwards Michael was knighted. He would charge into the office in the morning, swinging his arms as if he had just run a marathon. He would already have had a dozen new ideas while shaving and another dozen over breakfast. He sank into his old AMREF director’s chair and immediately started bombarding by phone his many contacts around the world for support for FARM.

FARM Africa’s first goat project in Africa.

The big difficulty was that while we were both ‘fired up’ with a desire ‘to make a difference’ as Michael put it, we disagreed on many things and it was hard to find an accord: Michael had a profound knowledge of Africa and passionately argued for the need to make dramatic changes to food production. His aim was to ‘green Africa’ by the year 2000. I, with my more cautious OXFAM approach, thought that in the long term more would be achieved by working with poor communities and helping them to farm more productively. But his vision was an inspired one and led us on.

Dick Sandford came to the rescue as we tried to agree on FARM’s role. He was a quiet and retiring man but he was firm in his convictions. He had worked in Africa and the Middle East for FAO over many years and had a broad perspective.

He believed that the key to development in Africa was to empower particularly marginal communities to find their way forward making use of improved agricultural techniques rather than massive projects run by teams of government and international experts.

Dick proposed to us that FARM should:

work with marginal communities to identify problems that might be amenable to new approaches such as improving the health of the great East African camel herds and raise the production of milk in goat herds by cross-breeding and better management.

FARM would raise the funds to do this and field small teams of specialists to work with communities bringing to them the latest most appropriate developments in research.

We should disseminate our successful experiences widely to influence governments, agencies and NGOs.

Both Michael and I responded enthusiastically. Michael saw the opportunity to use modern technology eventually on a grand scale, while I supported the idea of working closely with communities.

Dick then offered to help us plan and launch projects working as a volunteer. He played a major part in planning the camel, goat and forestry projects. His brother Stephen, who was an economist and had worked for the International Livestock Research Institute, joined us later to work on our Ethiopian programme.

We worked in Kenya, then expanded to Tanzania, Ethiopia and finally to South Africa. Our first project was in camel herding communities. This was led by Dr Chris Field, a highly individual but deeply committed livestock specialist. We had a plane – a Cessna 206 – which enabled Chris to move from one camp to another quickly, great distances being involved.

Development work with nomadic people had previously been provided from static centres. The pastoralists were expected to come to these centres but of course frequently did not do so. Dick proposed a novel ‘mobile extension’ approach. We had two camps each with their own demonstration herd of camels. The camps would move from clan to clan, spending a month or so with each clan. Training was provided in veterinary work, and hygiene and nutrition. We also provided guidance and some funds to enable the pastoralists to set up businesses such as butcheries.

Next, we launched a dairy goat project in Ethiopia which then spread out to neighbouring countries. Arguably our most significant contribution, this was led by the dynamic Dr Christie Peacock. This project involved up-grading local goats, kept largely for meat, by cross-breeding with milk goats such as Toggenburgs and Anglo Nubians, and advice was given on growing the necessary forage and providing veterinary care.

The project was designed for poor women, particularly the many widowed in Ethiopia by the very recent civil war. The milk from the goats strengthened family nutrition and the surplus could be sold. The result was that many women began to climb out of extreme poverty.

We became involved in forestry and many other projects including a large resettlement project in Riemvasmaak in South Africa, from which the community had been forcibly cleared by the government under its Black Spot programme.

Nelson Mandela was released from jail in 1990; apartheid came to an end in 1994 but South Africa began to change radically after Mandela’s release. FARM Africa was there during this momentous period.

We had helped the scattered community with an assessment on the agricultural value of the land which was occupied by the army for training because we feared the government would claim that it had no potential for farming. I attended the meeting in the Upington town hall where the government – still the old apartheid government – was to announce its decision. The hall was crowded and throbbing with expectation. A group of burly white farmers sat in the front row clearly expecting that they would gain access to the land. The chairman called the meeting to order. ‘We have decided that the land should be returned to the community.’ A wave of surprise swept the hall. The white farmers huddled together to decide how to respond. Their spokesman stood up and in a gruff, heavy tone said, ‘We will welcome them back.’ This for me marked the beginning of a new era.

I met Archbishop Tutu on two occasions, first as Archbishop of Cape Town and then as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He held, in both positions, a coffee break for all the staff including drivers and sweepers. He called me out on both occasions and I had 10 minutes of his undivided attention. He has large expressive hands, a powerful jaw and great warmth. Africa owes him so much. ‘In the new South Africa the poor may well continue to be neglected,’ he said sadly.

Michael developed cancer a year after we launched FARM and he died in 1989. I felt his loss deeply. We then moved the head office to the UK to be nearer the donors.

My first colleague in the UK was Camilla Boodle, a brilliant graduate from Jesus College, Oxford. She was over six-feet tall, tremendously clever, witty and a pleasure to work with. She stayed with us for a year. Tragically, she took her life at the turn of the millennium.

I ran the whole of the FARM programme until I stepped down in 1999.

I kept in touch with Dick after we both left Africa and frequently visited him at his farm, a small-holding run almost on African lines, near Ludlow. He died in 2009. He was one of the finest men I have known. Stephen is still with us but stricken by Parkinsons disease. Another man of great ability and integrity.

I must record the deaths of others, too. The Kenyan government would not renew Sister Annalena’s visa after the massacre and she moved to work in a Somali hospital. There she was murdered. Chris Morris, a member of our camel team, was another victim of African violence. He was murdered by car-hijackers, shot in the back of the head.

After four years, our income reached £2 million a year. In 2016, it raised £16 million and reached 1.8 million people in East Africa.

On retiring from FARM, I received an OBE from Her Majesty The Queen ‘for services to African farming’. Christie Peacock took over as CEO. The current CEO is Nico Mournard.

Looking back on FARM I feel more strongly than ever that our approach was and is highly relevant. It put faith in communities to be able to solve their own problems – with some outside assistance. It depended on committed teams working with communities, so different from many contract-workers on bilateral and multi-lateral programmes, and we acted as a witness in dangerous and oppressed places.

Lying in bed on a recent Sunday morning, I heard Michael Palin give the Radio 4 Appeal in aid of FARM. As usual he spoke eloquently. I had invited him to give his first appeal for FARM 20 years ago and he has remained a greatly valued Patron ever since. FARM continues to be marvellously alive and relevant.

I made great friends in Africa including Patrick Mutia who worked with us in OXFAM and FARM and Eliud Ngunjiri who left the Ministry of Livestock to work with us in OXFAM and then started a group to assist prisoners with resettling on release. I set up a UK group to support him but we couldn’t raise sufficient support.

A shanti settlement on the edge of the affluent Gulshan district of Dacca.

A pedal-driven water pump: low-cost irrigation for winter crops in the north of Bangladesh.

A Somali bull brought in for breeding by the FARM camel project. Somali stock produce more milk than the local Rendilie camels.

Gateway to the Riemvasmaak resettlement project.

A grape farmer on the south side of the Orange river pointing to the dry hills in the distance where the Riemvasmaak people will settle.

View across the highly profitable grape farms on the southern banks of the Orange river to the dry mountainous land on the north side where the resettlement project is taking place. At the foot of the hills is a dry area - an alluvial fan - which would be suitable for irrigated crops including grapes.