Growing Up

Mollie, my sister and I

We lived in Welwyn Garden City right through the last War and into the 1950s. My parents bought our house, the first they had ever owned, in 1936, full of confidence in the future. But the future turned out to be much harsher than they had imagined. War was declared. My father was called up and only returned for several weeks at the end of the war before leaving for good.

My grandparents soon joined us bringing with them their other daughter, Betty, and Ethel, an elderly much loved maid with St Vitis’s Dance.

Looking at the house now I wonder how we all fitted in. I cannot recall much tension and in fact those war years were happy for us as children although we all felt the absence of Andrew. I can remember the ‘blackouts’, the air raid siren and several bomb sites. But we were too young to think much about the war.

We attended Sherrards Wood, a local independent school five-minutes’ walk away. It was not a good school, no doubt suffering from the shortage of able-bodied teachers. I made very slow progress (I was mildly dyslexic) but Jenny achieved much more.

Jenny and I have always been close friends with only 16 months between us. In the early years we spent much time together. She married an artist and graphic designer, David Goad, soon after Caroline and I were married in 1965. They have a family – three sons and a daughter – and now live in a remote village in France in the Midi Pyrenees. We meet them frequently here and in France.

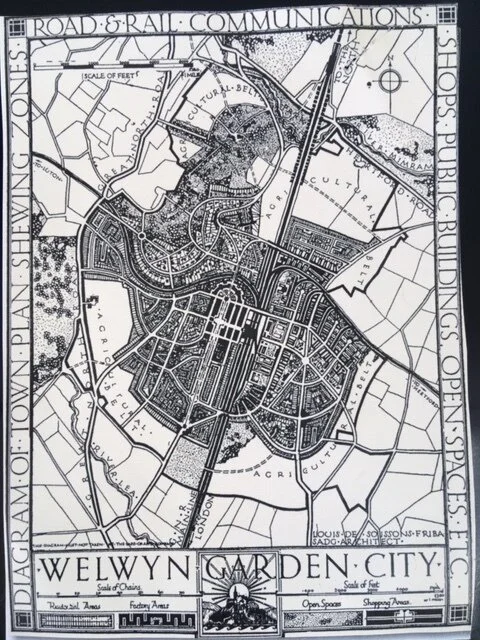

Childhood memories of Welwyn Garden City

Welwyn Garden City was a new town and an experiment in a different, more expansive type of living with many green spaces. We lived in a close on the north west corner of the town literally excised from an ancient woodland, still largely intact. There were six small houses, of which ours was one, and at the bottom of the close three larger houses. Many businesses had moved out of London at the outbreak of the war and three of our neighbours were from ICI. Later, after the end of the war, another ICI family moved into one of the large houses. Their son, Colin, had an eccentric manner and I found him difficult to relate to. He had a fine collection of coins. He is now a Conservative peer and a former Master of Jesus College, Cambridge.

A White Russian emigre and his wife – Mr and Mrs P – lived in an adjacent road and we had more contact with them than with most of our neighbours because their garden and ours had a common boundary. The Ps were passionate gardeners and founding members of the Soil Association which was launched in 1946 by Lady Eve Balfour who used to visit the Ps. They could be seen every day working in the garden dressed in the tattiest of black clothes. We looked out at their chicken house and an enormous compost heap, and keeping protective eyes on their garden, were two scruffy and fierce Afghan hounds. We were intimidated by them and called them the Woggers.

P was a journalist and writer and contributed to the national dailies. Betty travelled up to London frequently with P and they were on very friendly terms. Apparently on one occasion he invited her to become his mistress but she declined. My mother regretted her decision. 'It would have been a great opportunity for Betty,’ she said. A surprisingly liberal position for her to take at that time.

Jenny used to visit Mrs P after her husband died and she would relate stories of life in Imperial Russia. While she looked to us like a Russian peasant, at home she was transformed when she set off on a trip to London, emerging like a butterfly from a chrysalis on high heeled shoes and dressed in a well cut suit, a hat and veil.

P was a journalist and writer and contributed to the national dailies. His speciality, no doubt, was the development of the new Soviet economy. P finally had a stroke and I remember him slowly and painfully pushing a barrow-load of green waste from other houses for his great heap.

My great friend at that time was Ansel, the son of a geologist who later became a professor of geology at a northern university and received a knighthood. They lived five minutes away. Ansel’s parents were devoted musicians. A grand piano filled much of the living room. Ansel’s father would play passionately and it seemed to me he occupied another world. We had many good times together but our friendship was brought to an abrupt end when Ansel’s parents learned that our parents were separated.

I never greatly loved Welwyn but when I return I realise it means more to me than earlier I would have admitted. Echoes of the past from that period frequently come back to me like phrases of music, some to be cherished, others irritating and best forgotten.

I began to re-discover Welwyn Garden City in the months before my mother died. She had a small flat in a care home above the Campus, one of the central features of the new and second garden city designed by a leading architect, Louis de Soissons.

In the early years Welwyn drew in prominent people such as the Heron family, founders of Cresta Silk, whose son, Patrick, became a leading artist, and George Bernard Shaw who came over from his home in nearby Ayot St Lawrence to browse in the Welwyn Stores bookshop. Also, during the war, the families of ICI senior management moved to Welwyn.

Looking south from her flat you could see the double boulevard with the big department store on the eastern side and de Soisson’s beautiful church, the spacious red brick building, St Francis of Assisi, on the western side. To the east the elegant and distinctive clock-tower of the original council offices.

To the north of her flat a single road passed over the White Bridge beneath which the now defunct branch line ran to Harpenden and Luton. I remember lying in bed and listening to the train puffing up the gradient.

Everywhere the trees planted after the city was founded in 1920 are now mature.

Running over the bridge you would come to Sherrards Wood School, which we attended for a while, and beyond, the purely residential quarter of the city leading to the fields and woodlands of Hertfordshire.

I ran in the early morning from the flat to different parts of the city. Half-forgotten memories flooded back and I began to be aware of the beauty of the city which I had once dismissed in my ignorance as ‘boring’ and ‘suburban’.

West Germany

In 1951 Andrew brought us out to West Germany where he was stationed and we were sent to a British Forces school, King Alfred’s, on the Grosser Plöner See in Schleswig-Holstein, built originally by Admiral Doenitz as a U-boat training school. The layout of the school was still in the form of a naval training centre with a quarter-deck and flag pole at its heart. Vast numbers of wild fowl gathered on the lake. We would watch skeins of geese descending noisily on to the water and there I learnt to sail yachts inherited from the German navy.

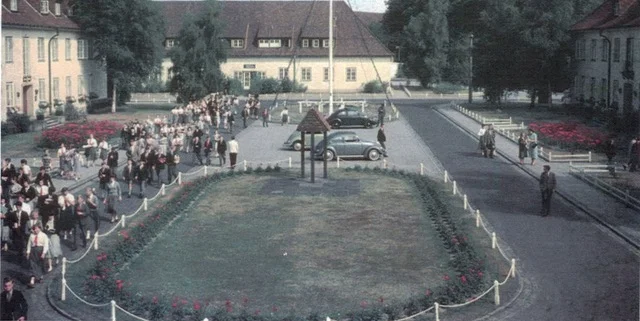

The quarterdeck, King Alfred’s School, Plön; before the Second World War it was a cadet training school for the German navy.

We could see the medieval town of Plön with its great white 17th century castle, its black cupolas clearly visible on the far side of the lake, but we never visited it or learnt anything about its history and the high drama of more recent years. I now know that before World War II the castle had been a political training institute under the Nazis. Doenitz was based there in the war and took over as head of the ‘Flemsburg’ government for a few short weeks following Hitler’s suicide, until the new Allied administration was formed.

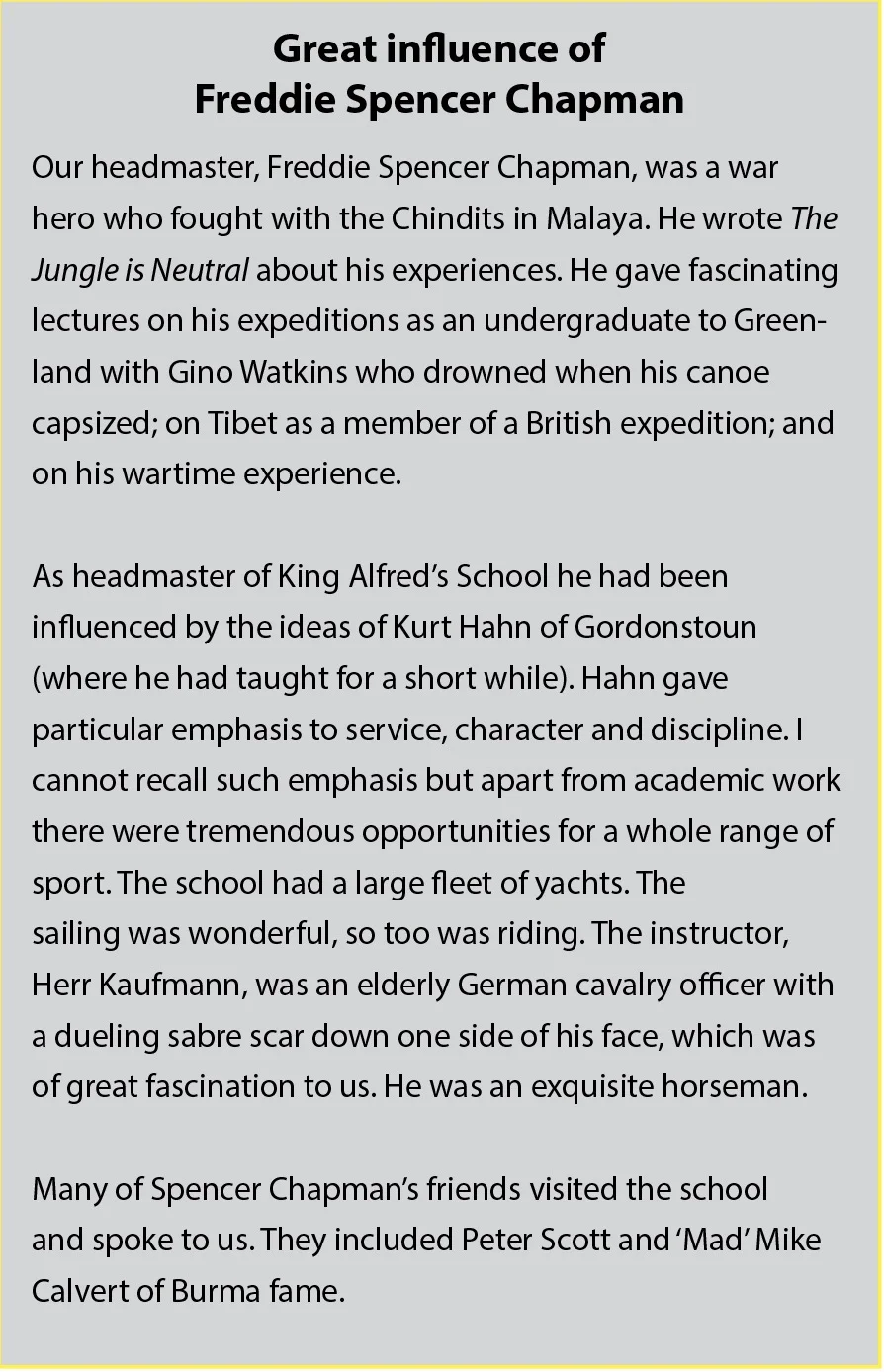

King Alfred’s was a unique school. There were children of 20 different nationalities, half a dozen religions and boys and girls from many different backgrounds and abilities. Formed shortly after the end of the Second World War by Freddie Spencer Chapman, it developed and retained good relations with the German community which must have required great skilI in view of the recent past. Franz Graf Waldersee, whose family have estates in northern Schleswig-Holstein, has told me that as a child he was free to visit Spencer Chapman at the school and was much impressed by him.

King Alfred’s was a vast improvement on our first school and I began to respond to better teaching.

We unruly children found Spencer Chapman a remote figure and we had little direct contact with him. Andrew met him for a drink on a visit to Plön. He ‘didn’t care’ for him greatly, but I suppose professional jealousy was to blame. Today, I regret that we were so indifferent to him – and, with hindsight, I recognise the profound effect of his influence on me: he introduced me to the wider world and to the adventures and possibilities that existed beyond my immediate reach. Years later Spencer Chapman committed suicide, apparently to spare his wife the burden of looking after him as an increasingly sick man. Earlier, his son Stephen had disappeared without trace in Saudi Arabia.

Another figure who made a deep impression on me was Group Captain J.H.O. Jones who awakened my interest in classical music. He played Debussy and Ravel on the piano at the start of assemblies. During his music lessons, he played to us and told us stories about his life as a pilot in the RAF and as the commandant of the Sunderland flying boat base in Scotland. He was a sad solitary figure, wearing an old camel hair coat in the cold weather, and seldom smiled. He had had one son, an ace-fighter pilot, who was shot down and killed in the war.

The Black Watch

We returned to England after two years. I was sent to crammers in London – Andrew’s earlier plans to send me to a ‘good’ public school had failed – and Jenny went to a girls’ school in Surrey. This was an acutely depressing time for me and one of poor academic achievement. In 1957 I was called up for National Service. I joined the Black Watch, Andrew’s old regiment and later, after training at Eaton Hall, was commissioned back into the regiment. I served in Scotland and Cyprus in the later stages of the Emergency.

Regimental life amazed me: the suave, assured sophistication of my fellow officers, the magnificence of the parades, the brass and pipe bands, the mess dinners around tables set with ornate silver with a piper playing to us as we ate, lunch with the Queen Mother when she visited us before we left for Cyprus, active service in the Troodos mountains and on the coast where I commanded a police station in an orange grove.

A Visit by HM The Queen Mother, Colonel-in-Chief, 1st Bn the Black Watch, at Redford Barracks, Edinburgh, 18 October 1958, when Her Majesty took the Salute prior to the Battalion’s departure for Cyprus. I am ninth from the left in the back row.

Royal Agricultural College

I had decided while in the army to go into farming and I attended the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester, to study for a diploma in agricultural science. A requirement was that I first worked on a farm for a year and this I did in Kent. The farm was of the old-fashioned sort with limited mechanisation and much manual labour was required including muck spreading and hoeing of vegetables. Coming from the elitist world of the Black Watch, life as a farm worker was quite a change. I would have gained more from working on a modern farm but I certainly learnt a lot about farming in the raw.

My time at Cirencester was not quite as stimulating as it should have been. I felt ill-at-ease and my social life was somewhat fraught. At the end of the two-year course I applied for a job as an assistant manager on a tea estate in India. I had no intention of spending my working life there but I wanted to travel.

Freddie Spencer Chapman, my old headmaster at King Alfred's Plön. He is filming in Lhasa in 1936. He was a great influence on me and I would rather use this shot than one of him as a middle-aged school teacher.

Welwyn Garden City in the 1920s - an early experiment in new town development. We lived in the northwest corner of the city.

Roderick Thomson died in December 2013 aged 75 as a result of complications following abdominal surgery. We and many of his great circle of friends attended his funeral in Yorkshire. It was a sad and sudden event and there was a deep sense of loss.

He and I first met in 1957 as National Service recruits at the Black Watch Training Company at Perth. Compared with most of the other recruits who came from rural eastern Scotland, and from Glasgow, we were southerners. Also, Roderick had attended my father’s old school at Highgate. He was my most significant and valued friend.

As a mark of his singularity he would go through cuttings from north London sent to him by his mother.

He was perhaps more ill at ease than I in the rough of barrack life. He was not selected initially for officer training. I went off to Eaton Hall, and then back to Perth with a commission. Roderick followed and was later commissioned into the Royal Fusiliers.

After service in East Africa he went to Camberwell School of Art. He progressed first to Unilever in London and from there to Bradford Grammar School where he taught English and Art.

In these early years while we were in London we both married and met a great deal. But preoccupation with family life and careers gradually came between us.

Sadly, I found Roderick increasingly difficult to relate to as a friend. He was by his own admission an ‘interrupter’, not through rudeness but as a result of an intense interest in life, and a sparkling intelligence. He was increasingly restless, seldom staying still for more than a few minutes.

Roderick developed an unusual gait, slightly lop-sided with his left arm held behind his body, as a friend remarked, like the rudder of a boat as if to steer him through the vicissitudes of life.

His circle of friends and supporters and societies was immense. It included the Victorian Society, Migration Watch, Prayer Book Society, English Officers Society. He was a strong traditional Anglican and, for a time, was a member of the Bradford Diocesan Synod. He regularly attended the Aldeburgh Festival.

Despite his wide range of interests and restless nature he was the greatest and kindest of friends, always ready to give the wise advice and support. I would turn to him at times of difficulty, often through long telephone calls. He arranged introductions for me to meet leading figures in the north when I was thinking of applying for a public appointment and accompanied me to the meetings.

Roderick and his wife Ursula had two boys, Duncan and James. Tragically, James developed muscular dystrophy and died at the age of 18. Duncan has settled down and has a large family. Roderick and Ursula’s marriage was tense and unhappy and ended in divorce. Angela McKenzie became his partner for the remainder of his life.

A strong influence on Roderick was (later Sir) Kyffin Williams, his art teacher at Highgate. His interest in art only increased at Camberwell. He produced some fine works with bold colours and forms but he decided not to continue as an artist, a decision his friends at least regretted. But he continued to keep contact with Sir Kyffin and on one occasion took us to meet him at his cottage on the Anglesey shore of the Menai Straits.