Lincoln College Choir

On 14 May 2022 we celebrated the life of Richard Brett (1567-1637), who served Quainton Church as Rector throughout his life and who was also one of the translators of the King James Bible.

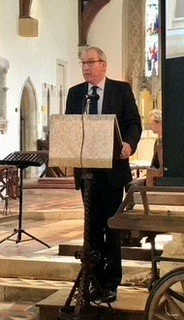

We were honoured by the presence of Prof Henry Woudhuysen, Rector of Lincoln College, where Brett was Fellow. He spoke of Brett and his world (see speech below), and the College Choir sang choruses from the Messiah, Handel’s great masterpiece from which he drew the texts for the choruses.

Over 60 people joined us for the celebration. It was a wonderful day and a fitting tribute to a great man, long dead but not forgotten.

Richard Brett and his world: a wonderful restoration - Henry Woudhuysen

I am greatly honoured to have been asked to say a few words about Richard Brett whose monument in this beautiful parish church has been expertly conserved by Imogen Paine, work generously funded by Dr Basil Smith, who has long family ties with the parish of Quainton.

Professor Henry Woudhuysen

When we think about religion in the sixteenth century, we need to consider the central Reformation project of biblical scholarship. For the vast majority of people, a better understanding and a closer familiarity with the Bible’s teaching was at the heart of daily life. The scholars who sought to make this possible used the printing press to disseminate the fruits of their labours in editions, translations, and commentaries. This work was undertaken throughout this country and on the Continent, by both sides of the confessional divide, by Protestants and Roman Catholics, in learned languages, especially Latin, and in the vernacular.

In Germany, it was Luther’s translation of the Bible into the vernacular that made it available to all – to those who heard it read and to those who could read it themselves. Luther’s translation did more than instruct and console; it created a standard form of the language that would help to unite the different German-speaking countries and states and eventually to forge a nation. In England, translations of the Bible were produced by individuals, such as William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale, as well as by groups of churchmen and scholars. The results – the Great Bible, the Geneva Bible, the Bishops’ Bible, and so on – all contributed to the development of the doctrinal beliefs of the Church of England and the formation of a common culture and, in time, to a United Kingdom.

Yet the number and variety of different forms of the Bible in English told against the need for conformity and universality. These were some of the problems that King James I faced when he called the Hampton Court Conference in January 1604; on its second day, he was told that the available versions of the Bible in English were ‘corrupt, and not answerable to the truth of the original’. His response was to commission a new translation of the scriptures that was eventually published in 1611 and is generally known as the Authorized Version of the Bible. The work of translation was to be carried out by up to 54 scholars based at Westminster, Cambridge, and Oxford; in each place, the work was shared by two groups. Our hero, Richard Brett, belonged to the first group at Oxford.

Brett (1567/8–1637) had been born in London to a Somerset family in the later 1560s; he came up to Oxford in 1582, matriculating at Hart Hall, aged fifteen, a year before the eleven-year-old John Donne joined the Hall (whatever became of him, I wonder?). Brett was clearly a fine scholar, gaining his MA in 1589, becoming a Bachelor of Theology in 1597, and a Doctor of Theology in 1605. We do not know exactly when he became a Fellow of Lincoln; it was probably soon after he had taken his first degree in 1586. He would have had to resign his Fellowship on marriage, and so he probably left the College in 1598. In the latter part of the sixteenth century, Lincoln was going through quite a distinctly Protestant phase and this may give us some insight into his religious inclinations. In the mid-1590s, Brett became Rector of Quainton, a perfectly usual move in those times for a Fellow of an Oxford college. By 1604, the year of the Hampton Court Conference, Brett had already been Rector of Quainton for about a decade and was to remain in the post here until his death in 1637.

In the first Oxford group of translators, Brett would have fond himself working not only with the then Rector of Lincoln, Richard Kilbye, but with the Rector of Exeter, Thomas Holland. The President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, John Rainolds, who had originally proposed the undertaking to King James, was the foreman of the group. Another member of it was John Harding, who was elected President of Magdalen College in 1607. Lincoln’s Rector, Kilbye, was a formidably learned man who became Professor of Hebrew at Oxford in 1620; at Lincoln, have his copy of the Basel 1498–1502 glossed Bible, partly in Hebrew, in four volumes in each of which he wrote ‘Ricardus Kilbie est verus possessor huius libri’ (‘Richard Kilbye is the owner of this book’). It seems likely that he used this scholarly edition in his work on the translation.

Brett would have been more than able to hold his own among these scholars and Heads of House. He had become, as Anthony Wood said, ‘by the benefit of a good tutor, and by unwearied industry … eminent in the tongues, divinity and other learning’. He was, Wood, drawing on the Latin inscription on the monument, continued ‘famous in his time for learning as well as piety, skill’d and vers’d to a criticism in the Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldaic, Arabic, and Æthiopic tongues’. In 1597, he published two editions at Oxford of Greek texts with Latin translations of pre-Christian geographical and historical works and of lives of Saints John and Luke. One was dedicated to Thomas Owen, a judge in London, a book collector, who was to die in the year following Brett’s dedication; the other to the Lord Keeper, Thomas Egerton, who was about to employ that other young man from Hart Hall, John Donne as one of his secretaries. Both Owen and Egerton were prominent members of Lincoln’s Inn and Brett may well have had links with people in legal circles there. Brett’s last publication at Oxford before the Authorized Version was a short work of Christina doctrine, written in Latin and tactfully dedicated to the new King in 1603.

Brett and his Oxford colleagues in the first group were tasked with translating the seventeen books of the Old Testament, from Isaiah to Malachi. The first five of these are the Major Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel) and the twelve Minor ones, of which Jonah may be the best known for its story and Habakkuk most admired for its debate between God and the prophet. If some of the most familiar phrases in English – ‘the salt of the earth’, ‘the apple of my eye’, ‘the fly in the ointment’, ‘new heavens and a new earth’, ‘holier than thou’, ‘Set thine house in order’, ‘sour grape(s)’ and ‘his teeth shall be set on edge’, ‘a wheel in the middle of a wheel’ – did not appear for the first time in the version of the Prophets in 1611, it was the Authorized Version that made them popular and kept them before the eyes of readers and the ears of listeners for the next three centuries or so.

Charles Jennens’s libretto for Handel’s Messiah (1741) in which 21 of the oratorio’s 81 verses come from Isaiah, including the opening ‘Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God’ and the wonderful ‘For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace’. There are also in the Messiah two or three extracts from Malachi (‘But who may abide the day of his coming?’), Haggai (‘I will shake all nations’), and Zechariah (‘Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem’). All these were the work of the Oxford group, and if we cannot be sure which passages from the Prophets came from Brett’s own pen, he was certainly involved in the larger task of rendering their words into English. Jennens’s libretto for the Messiah captures something of the powerful poetic and reflective language of the books.

Brett died in 1637 aged 70. Wood describes him as ‘a most vigilant pastor, a diligent preacher of God’s word, a liberal benefactor to the poor, a faithful friend, and a good neighbour’. He had married Alice or Alicia Brown, the daughter of a baker, a man who was three times Mayor of Oxford; they had four daughters. The oldest, Elizabeth, married William Sparke, the Rector of Bletchley; Anne married Humphrey Chambers, another priest; the third, Margaret, married the magnificently named Dr Calybute Downing; and Mary, the youngest, married Thomas Goodwin of Elwell in Oxfordshire. Brett’s monument was erected by his widow of 39 years.

There the daughters pray, kneeling on hassocks facing outwards, while their father and mother kneel at a desk or prie-dieu facing each other in prayer with books in front of them and behind them. The books are open and have what were meant to represent dyed silk ties with which to keep them closed. The two books behind the married couple bear a partially hidden inscription that probably reads ‘Verbum meum Æternum’ (roughly translate as ‘My Word is Eternal’). It is hard to resist the temptation to think that the books were intended to represent copies of the Authorized Version. The tomb is made of alabaster and black marble; it has been coloured, and on the frieze there are inscriptions in Hebrew, Greek and Latin.

The restored memorial

In his 1960 volume of the Buildings of England covering Buckinghamshire, the great architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner drew attention to Quaniton’s church as being ‘exceptionally rich in late C17 and C18 monuments’. And so it is, with its splendid array of five or six really magnificent tombs. Pevsner did not mention the earlier one to Brett and his family. In the revised edition of 1994, Elizabeth Williamson and Geoffrey K. Brandwood briefly describe it without comment. Now that it has been so magnificently restored, perhaps it will gain the attention that it and Brett’s own contributions to the parish, to scholarship, and to the English language all deserve. In restoring the monument to Brett, the parish has done a wonderful thing of which you should all be very proud.

H.R. Woudhuysen, Rector, Lincoln College, Oxford -14 May 2022