Lottie

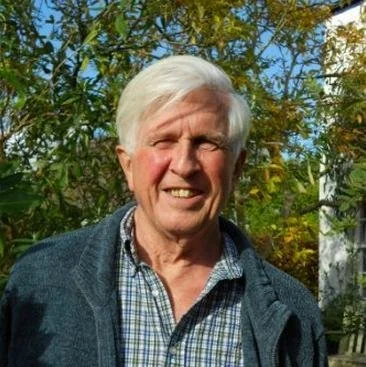

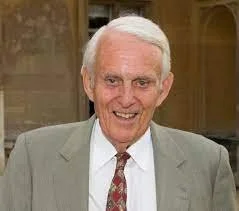

Dad was extraordinary – unique, remarkable, curious, visionary – and in so being, he gifted us an extraordinary childhood. He was adventurous, an explorer, and nowhere was off limits – the more inaccessible the place, the more fascinated he was. His working life across Africa and the Indian subcontinent allowed him to travel widely, and he often took us with him.

A good chunk of our childhood was therefore spent in a long-wheelbase Land Rover, bouncing on a wheel arch, or squished into the footwell. Throw a mattress into the back and you have a family holiday. As you can imagine, the roads to remote destinations are challenging, even perilous at times. But while there are roads that even trusty Land Rovers draw the line at, turning back was not in Dad’s vocabulary – to the rescue would come a bullock cart, or an overcrowded bus, and on we’d go.

His curiosity was unbound by such prosaic concepts as safety and practicality, and so we went to places very few others did.

Our first trip to India in the mid 1970’s was to Kashmir, where we stayed on a houseboat and took shikara boat rides through floating gardens. We travelled up into the hills so Dad could go fishing amongst the apricot trees; his guide, a man who had lost his nose to a bear.

Because of Dad, we have seen the sun rise over Mount Everest, near Darjeeling, where, in earlier years he had worked as a tea planter. We watched from Tiger Hill; it was bloody freezing. The coldest place on earth.

He took us to Sikkim, in Northeastern India, which borders with Tibet. We were the only people staying in the large hotel and visited a monastery over the Buddhist New Year.

We stayed in The Grand Hotel in Rangoon, a relic of the British Raj. From here we travelled up country into a restricted zone to visit a project, leaving and returning under the cover of darkness.

We stayed with the King and Queen of the Mongs, a tribe in the hill tracts on the Burmese/Bangladeshi border. Another restricted area, requiring passes to visit. We ran barefoot through rivers and mud with the local children, rode on elephants and all slept together in the most enormous bed imaginable.

He took us to Lake Turkana in Northern Kenya. A sparsely populated area and the largest permanent desert lake in the world. A major breeding ground for Nile crocodiles, hippo and many venomous snakes, a harsh and astonishing environment.

And the intrepid trip to Ladakh with me when I was ten. A 24 hour bus journey up a treacherous winding single track mountain road. Hurtling along, the driver entrusted our safety to Allah, so too did we as we observed carcasses of buses down below, and prayed no vehicle was heading towards us from above. From Leh we trekked on ponies, further into the mountains and stayed in a house guarded by a rabid dog. The dog was held back by jamming a stick into its mouth so that we could run past. Terrifying for an anxious ten year old child, but Dad as always took it in his stride.

It seemed to us that Dad was frightened of nothing. His demeanour as he drove us away from a charging rhino – he liked to see how close he could get to dangerous animals – betrayed much less panic than when we were going to make him late for church, or, more latterly, when he wasn’t able to check his emails.

He calmly – blithely, perhaps – marched us into adventure. He may not have been fearful – but we were! As the eldest, I was terrified. Harriet says she always knew he’d get us out safely – Jo says she didn’t know anything of the sort. Cassie had the blissful ignorance of youth.

There were many nights of terror, sleeping in tents in the African bush, with insects the size of rodents flying clumsily into us, and hippos snuffling and snorting on the other side of the canvas. We would lie awake, anxious, as we listened to the banging of saucepans by the night watchmen as they scared away the advancing elephants.

On one outing, Dad hopped out of the car to go and look for crocodiles in the river Athi, leaving us trembling with fear. Would he be snatched by one of these formidable beasts and never be seen again?

And then there was the epic family journey to Lamu, on the Kenyan coast. The rain was heavy and large, murky bodies of water were collecting along the slippery, black cotton soil road. How can you know for sure if they are too deep for the car to safely pass through? Why, send your horrified children through first on foot…

Maybe the one thing he did fear was inaction – not being able to do something, to change things for the better. And so this great, great man forged ahead, with purpose and with interest, ready to work it out as he went, his wife and four daughters falling in behind.

Harri

Life abroad wasn’t all hazard or high stakes, of course, and not all memories feature a gung-ho father and a herd of dangerous animals. Simpler pleasures that were huge treats: a toasted sandwich and bottle of pop at the Nairobi Club, and trips to the drive-in cinema, smuggled in under blankets on the back seat, to watch the latest James Bond. And we don’t know many other people who travelled to their playgroup in a rickshaw.

We came home for good in 1986. We may have called Quainton ‘hibernation village’, but it was a welcome novelty for all six of us to be in the same country – apart from the many months each year Dad was back in Africa. But the home that our parents created in The Vine was no less extraordinary, just in a different way, and in unguarded moments, we will each still refer to it as home. It is comforting and constant, nourishing and full. Dad was proud of this home and loved showcasing it in action – which usually involved Mum feeding the five thousand.

The gravitational pull of The Vine is strong and it is little surprise that we have settled locally with our own families. Dad loved having us so close, but there was never any expectation – indeed whenever we appeared, his greeting was always one of surprised delight.

Dad loved flowers and plants, rare, exotic ones always grabbing his attention. When travelling in India and Bangladesh, he collected epiphytic orchids and smuggled them back to the UK in Mum’s sponge bag. To his frustration, these orchids never flourished in Quainton so he created the Tibetan plateau at the top of the garden, where he sourced and grew many Himalayan species more suited to our climes.

His garden was his pride and joy, and he eagerly took us on guided tours of the flowers in bloom. Dad was a tough, determined and feisty man and this was reflected in his choice of large and thuggish plants with the tendency to dominate if left unattended for too long, much to Mum’s despair as she fought for some space for her less vigorous specimens.

But there was also a great gentleness about him and thus amongst his treasures were a number of delicate plants that needed much nurturing to survive. He loved beautiful things and in early Spring, the garden puts on a breathtaking show of snowdrops, crocuses and anemones.

Beautiful, delicate things. He had an eye for intricate detail – and had opinions on fabrics. Before guests arrived, as Mum, elbow deep in kitchen prep marshalled us troops, Dad would disappear into the garden to cut the prettiest blooms and twigs for the table. His appreciation of beauty was with him to the end: speech had become difficult, but his eyes locked on to the intricate knitted pattern of my sweater – and my stripy socks amused him greatly.

He loved the sheer size of our family, enjoyed the company of his sons-in-law, and was proud of his grandchildren. After a lifetime surrounded by women, the boys were always a mystery to him. But as they matured and blossomed into young adults, they began to make sense to him and he thought highly of each and every one.

He relied upon IT input from Adam, Tom and Josh. He admired their ability to advise on all things tech, and grateful that they could sort out the endless computer glitches and retrieve lost and forgotten passwords. He enjoyed many an intellectual conversation with Caitlin. And Sean became his pond dipper, donning waders on a regular basis to move or clean the pump in the fish pond. He observed with amusement the youngest – Toby, Bea and Otta – from a safe distance; ‘they must exhaust you!’ he’d declare to their mothers.

But while Dad loved The Vine, and he wanted to stay there to his very end, he was still prone to flights of fancy – or, viewed less charitably, delusions of grandeur. Not one for conventional retirement plans, he’d fantasise about relocating to a near-ruined castle on the west coast of Scotland – ‘Mum’s not keen,’ he’d chuckle. Or a crumbling palazzo in Venice. Still not keen. So Quainton it was, and here he was content.

Jo

Dad was a great walker – we spent our childhood struggling to keep up. He loved the British countryside. It gave him such a sense of freedom and he would embrace all weathers. And long before wild swimming became fashionable, Welsh tarns and Scottish seas always tempted him in for a dip along many a hike.

Beagling with the Old Berkley Beagles was an important pastime in later life. And yet it presented Dad with a huge moral dilemma, which he never resolved – and we didn’t make it any easier for him. To be hunting such a beautiful creature as a hare did not sit well with him, but yet he loved to be in the countryside running across hills and fields with his firm and special friends amongst the Beaglers. In the early days he kept up with the hounds, unhindered by hedges and ditches – and barbed wire fences. Mum lost count of the number of breeches she had to stitch back together.

As years passed, he slowed down. One day not so long ago, he left the field early, alone, and got lost; seeing the road ahead, he forced his way through the hedge and climbed into the ditch – but getting out again was a struggle; his legs just didn’t work that way any more. Somehow he managed to roll himself out onto the road, where a bemused driver spotted him, helped him up and kindly returned him home.

And this is how Dad was throughout life and through his illness: he was blind and deaf to obstacles, sometimes ridiculously so – and he was determined that his ailing body would not dictate what he should and shouldn’t do.

Dad was an exciting person and had a great sense of fun. The lovely letters we’ve had tell of his humour, his gentle teasing, his sense of mischief. His was an exceptional humour: it spanned generations, and it was never dulled by age or by illness. He loved good company, had an ear and eye for the absurd and was always ready to be amused by life. He could also be fantastically rude, changing the topic as soon as he was bored, leaving us cringing in his wake.

He loved to dance – Farm Christmas parties, family weddings, ceilidhs. Indeed he was an energetic dancer, with a startling signature move that meant you might not want to get too close if you intended to keep both eyes. The memory of him playing air guitar at my own wedding is one I will always hold dear.

Dad was generous and thoughtful, and he knew how to buy beautiful presents for the women in his life – Liberty, his go-to store. At Christmas and birthdays there was always a present just from him – a carefully chosen book, or something exquisite – and I don’t think that’s all that common.

Cass

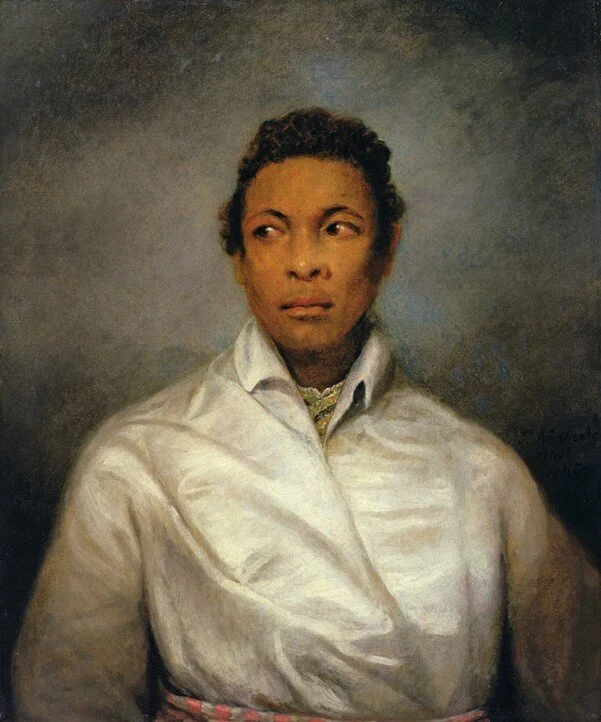

Dad was a man of obsessions – magnolias, and mermaids (he saw them everywhere, masquerading as land dwellers, usually identifiable by their blue nail polish), the Terminator films, Lampedusa’s The Leopard. Obsessive too about his projects of the moment. On these, he could be maddeningly, infuriatingly relentless, but it reflected his full and busy life.

He was a giant of a man. A superhero who attacked life – a father who could fly a plane, stride through bogs, navigate you safely off a foggy mountain, build you a cupboard with a secret drawer, kill the snake in your bedroom with a hockey stick but, even when at his frailest, rescue worms on pavements, lured out by the rain. A father who smuggled animal skulls out of the Nairobi National Park for your interest; who refused, even at gunpoint, to get out of the car as he was sitting on a pile of cash destined for a project; who kept his head and didn’t break stride when followed home by a mountain lion. A father who blew his small inheritance on a beautiful sundial in memory of his own mother; a man who loved kippers, and green jelly, and who was reprimanded by the secretary of the Byron society for taking too many sandwiches. A father who doubled as a birthday cake engineer – even his cakes were dynamic, although taste was occasionally compromised: for Mum, the beetroot gorilla that beat its chest, for me, the duck that traversed the room on a zip wire, for Jo, the submerged (and ultimately soggy) whale with functioning blowhole…

It goes without saying that none of this would be possible without our incredible mother at his side – but Dad led us out on the ride of a lifetime. And put simply, he was ours, and we were his, and for that we will all be for ever grateful.