In the Lee of Conflict and War: Family Roots, Part 1

My great-grandfather, Charles Campbell.

My Parents

Crossing the Equator in a troop ship, Andrew dressed up as an angel, covering his large form with a white sheet and bearing a halo made from cardboard. He won first prize and caused much hilarity. His large nose and small, closely set dark eyes gave him at certain angles a slightly diabolical look.

He had many friends despite dark moods and was tremendously good company and yet as a father was unreliable and negligent. My sister, Jenny, and I loved him but tensions created by his leaving my mother and re-marrying stood between us. I think he loved us too but in an awkward way.

Andrew was born in 1911 in Highgate, London. He was one of eight quarrelsome siblings. His father, a stern, God-fearing man, was a solicitor with the family practice in Dean Street, Soho. They lived in a large gloomy house with a mulberry tree in the garden.

He and his brother, Stephen, followed their father into the legal profession although Andrew would have preferred to be an engineer.

Andrew met our mother, Mollie Speaight, at St Augustine’s Church in Highgate and they were married in 1936. Both families were strong Anglicans. Andrew served as an altar boy and ran the church Rover pack. Mollie was the gentlest of women and no match for the wily, sensual Andrew. She became the secretary to Sir Robert Johnson, Deputy Master and Controller of the Royal Mint.

Mollie at her wedding.

My father did not return to us at the end of the war except for a visit of a few weeks when he pressed my mother relentlessly to agree to a divorce. He then returned to the Middle East. After several years Mollie agreed to do what he wanted and Mary became his second wife. He was transferred from the Black Watch to the Directorate of Army Legal Services and was eventually promoted to Deputy Director, Middle East, with the rank of full Colonel. He excelled in court work.

While he was unscathed by the war, two of his brothers were killed: Paul, a bomber pilot and Peter, a submariner.

Mollie with me at a family wedding in the early 1990s

Mollie was highly intelligent and witty. With more support she would probably have gone up to Oxford and led a different life. A bad marriage and divorce – which in those days bore a heavy stigma – together with lack of money, put a great strain on her, while Andrew by contrast was leading a glamorous life in the Middle East as a successful and attractive officer. There was much drinking and dancing and great sporting events including wildfowling with Prince Philip, and he was accompanied by Mary, who was beautiful and younger than him (Mollie was eight years his senior). Back in England, Mollie struggled with bringing us up in the suburban world of Welwyn Garden City.

After the divorce, which Mollie had resisted for several years on religious grounds and the vain hope that he would return to us, we began to see Andrew again. We enjoyed being with him. I particularly appreciated his masculine way of life and the many fishing and shooting expeditions. We also became very fond of Mary. But we were now living in two very different worlds and this was deeply unsettling.

North Wales

Bored with army life, Andrew took early retirement in 1955 and bought Hafod Uchaf, a barely accessible small hill farm on the slope of Moelwyn Mawr in Snowdonia. With the help of two charming and rustic local farmers he ran a flock of Welsh Mountain sheep and a single-suckler herd of Welsh Black cattle.

Access to Hafod was up a steep and winding Roman road. Andrew drove up and down it in a formidable and thirsty V8 Allard and an ex-US army Willys jeep. Both were open to the elements, having neither hard tops nor hoods.

The social world was narrow and unusual. The centre for the English immigrants was the Bondanw Arms in Llanrothen and gathered there was a colourful, rackety and impoverished assortment of people, mostly aspiring writers and artists: black-bearded Christopher Wordsworth who later became a well-known reviewer for the Guardian and Observer; Jeremy Brooks, a novelist and later the Literary Manager at the Stratford-upon-Avon Shakespeare Memorial Theatre; Admiral Sir Casper John, a son of Augustus John, and Hamish Moffat, a restorer and racer of Bugattis.

There are many stories of this group, but the the best possibly is of the spiky and clever Christopher Wordsworth. At that stage in his life he was severely impoverished and tended to overstay his welcome in his friends' homes and make advances to wives and girlfriends. His friends tried to put an end this by sending him in to exile in an exceedingly remote cottage on the Bala moors. Survival was difficult and being an excellent fisherman he worked the local streams. On one occasion he was chased as poacher by the local landowner. They came face to face but all was well. Both recognised that the other was wearing an old Rugbeian tie.

Andrew loved the company of the Bondanw circle, so different from an army mess or his London club, and he would spend hours propping up the bar with them. Mary did not share his enthusiasm, remembering perhaps the glamorous life she had led in Alexandria, and would sit in acidic silence in a corner of the pub drinking numerous gins and tonics. Jenny and I were fascinated by the Brondanw community but perhaps a bit out of our depth.

Andrew started a building company with an army friend which restored old properties. It did not survive for long and Andrew and Mary then moved from Hafod to Y Dduallt, a fine 16/17th century manor house on the southern flank of Moelwyn Mawr overlooking the Maentwrog valley.

The Brondanw was too far away for quick visits; also the Brondanw circle was aging, borne down by family life and the demands of careers, and much less fun. Andrew was more sober too, aspiring to the life of a country gentleman but on the slenderest of incomes.

Dduallt lay just below the derelict upper reaches of the Ffestiniog Railway. The only access was a goat track but the old Ffestiniog track was sound enough for a handcart to be pushed up to the house with their furniture. He also started work as a solicitor for Merioneth council.

Andrew loved building and he gradually restored Dduallt, largely with his own hands, and helped the Ffestiniog Railway Company re-open the line up to Blaenau Ffestiniog. The track had been inundated by a pumped-storage generating scheme. Andrew already had an explosives licence secured for clearing a road up to the house. He offered his services to help blast the cuttings for the new line. He did this quite casually without a thought for his own safety, never wearing a helmet.

Andrew on the family’s Ffestiniog Railway platform.

Andrew driving his train.

He let the barn behind the house for the volunteers working on the new track. In return, the railway built a station for him above the house called Campbell’s Platform. He then bought an old narrow-gauge diesel locomotive from a gravel pit near St Albans and ran up and down the track to Tan-y-Bwlch station. His involvement in the Ffestiniog Steam Railway and his subsequent daily commute is chronicled in the 1974 BBC Documentary The Campbells Came By Rail.

After he retired he spent most of his time working on the house and seeking to bring out imaginary ‘medieval’ features. Much later a dendrologist took core samples from the beams to gauge more accurately the age of the building. This proved impossible because Andrew had chipped away at the beams to make them ‘older’.

Andrew trying to convince Sir Clough Williams-Ellis of the ‘medieval ‘ origins of Y Dduallt, the family house, at a meeting of the Merioneth Historical & Record Society in 1964. Sir Clough was a well known architect and creator of the nearby Italianate resort, Port Merion, in North Wales.

The house was intensely uncomfortable and cold except for Andrew and Mary’s bedroom. His wine cellar was an old bread-oven sunk in the thick walls of the house. We would complain when he poured out almost frozen red wine. ‘But it is at room temperature,’ he would protest.

Near his death, Andrew and I were drinking whisky late at night. ‘I have had only one problem in my life,’ he said. I didn’t reply, anticipating some embarrassing revelation. There was a pause. He then repeated himself. ‘Well, what was it?’ I asked warily. ‘The fact is I have never had enough money!’ So there it was, a major source of his black mood and melancholy - or possibly a dark joke.

He was indeed perpetually short of money but somehow kept afloat using his considerable charms to attract loans from family and friends. ‘The more you ask for the more likely you are to get it,’ he advised me.

Andrew’s health was not good latterly. Having a doctor who was as old as he and not conversant with modern medicine did not help. He developed angina and continued heavy building work at Dduallt. His luck ran out at the age of 71 when he died peacefully in his sleep.

He had a splendid funeral in the beautiful church in Maentwrog in the valley below Dduallt. A piper from the Black Watch territorials played a lament. A granite obelisk marks his grave.

The sundial was designed and made by Mark Frith. It is positioned so that a shadow is cast on the dateline on Mollie's birthday, 8th February. Click here to read more about making the memorial…

Mollie died in 1991 and her ashes are buried in St Francis of Assisi in Welwyn Garden City where she worshipped throughout her adult life. While I loved her deeply I was not always kind to her, and this I regret greatly.

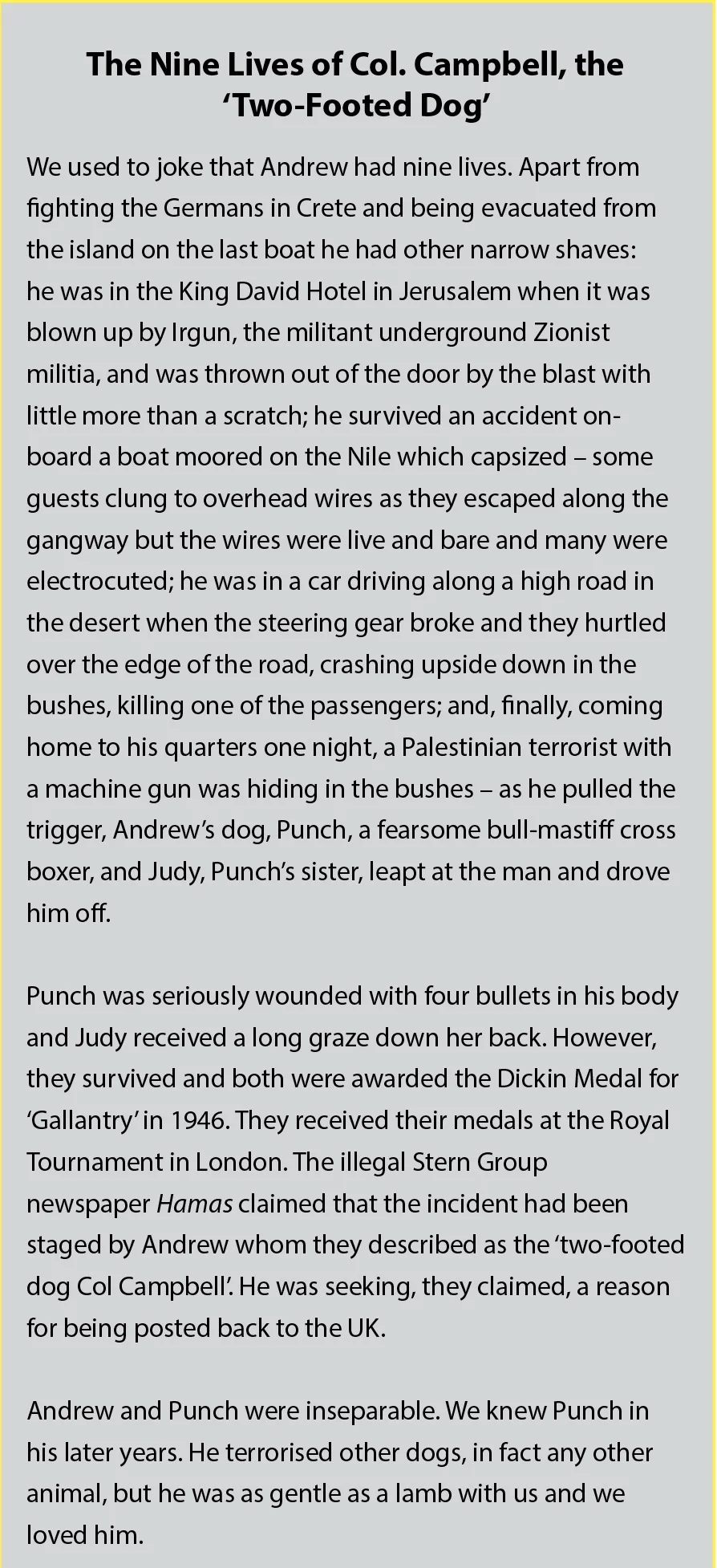

Punch receiving his Dickin medal for bravery at the 1946 Royal Tournament, accompanied by Andrew and a Black Watch piper.

'Andrew in North Africa, cleaned up after the battle and retreat'